Fake it 'til you make it

Unclenching, Part 3

This is the third part of a series.

Doubling down is robust. By leaning harder into our favourite actions, we minimize the effect of outside interference whose exact form we can’t predict. But how do we know our favourite action—our best model—is really what it claims to be? How do I know “I can’t predict”, or find a better way?

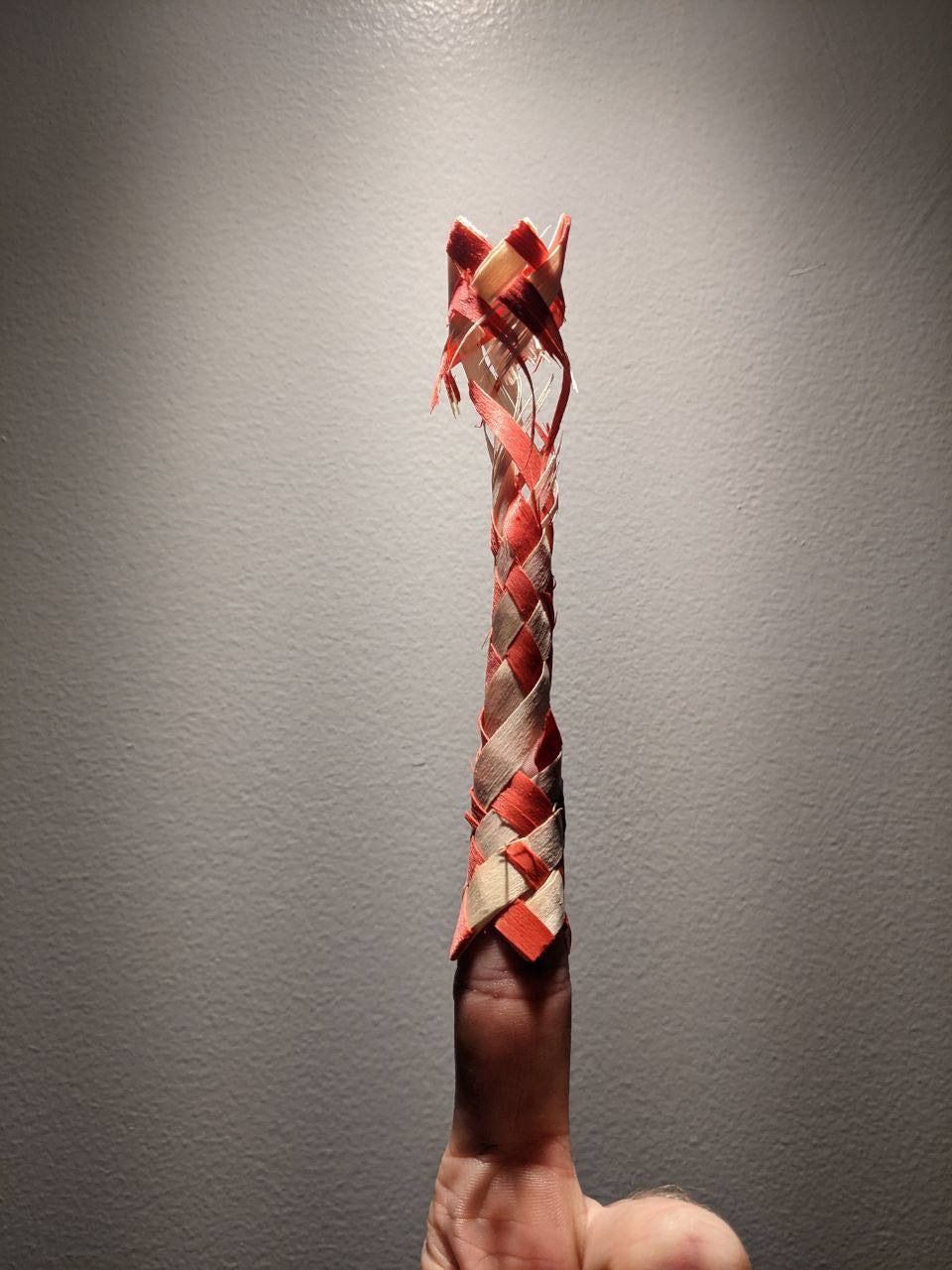

To escape a finger trap, a child ultimately needs to discover a new pattern, like push inward and use my thumbs to hold the trap while I pull my fingers out. Unlike someone making separate movements that only last a second or so each, affected by unpredictable disturbances that cannot be entirely compensated, the child is immersed in a continual situation. We know they have time to recognize their confusion, experiment with movements, and learn the solution—for good.

What counts as "outside interference" to a child pulling on a trap? Well, anything that interferes with pulling.1 Any shift in their attention to alternative approaches. Any experiment involving sustained pushing, that could reveal the winning strategy.

The narrowing of attention and action may be exclusionary of alternatives.2 We only have so much attention, and distractions are dangerous where tigers are concerned. "Pull harder" bets against the finger trap having an accessible and efficient solution. I don’t have time for that right now.

Taking the time to experiment and learn would save the child the energy and futility of pulling harder for who-knows-how-much-longer. But how do they know that there is even a solution that needs learning? How long will the experiment take? What evidence have they seen of an alternative, until they've tried it and it works?3 Maybe pull-harder will keep working like it always has. Our hindsight tells us it's improbable that this kid will defeat the trap by pulling harder. But at the moment, they don't seem to believe it.

If the kid's IQ is high enough, will they simply see past this obstacle immediately? Perhaps. Then they'd move on to the next challenge, and the next, until the metaphorical traps become subtle enough that they can no longer merely peek over the horizon at the solution. Wherever such an impasse is met—a pressing uncertainty without a ready remedy—even a genius kid can only lean harder into what they’ve already got.

And maybe they're having too much fun being trapped.

Does the prophet see the future or does he see a line of weakness, a fault or cleavage that he may shatter with words or decisions as a diamond-cutter shatters his gem with a blow of a knife?

- Dune

In the theory of active inference, prediction and action are not entirely separable events in a sequence, but dual views on the same thing.4 Different words for changes in a living process.

I predict that food should be in my stomach, but my senses tell me my stomach is empty. This mismatched prediction is tension in the process that is my body. Action is the tension resolving itself—the result of a force applied across the process. I feel the tension of hunger, and my hand is driven to reach for an apple, which I start to eat5. I'm still predicting there'll be food in my stomach, and now I sense there is. No more mismatch.

Predictions are about the world. Actions alter the world. We can act to make the world more predictable. We move, and in moving we create context. We enact structure.

Legislation and government aren’t primordial parts of physics, or even psychology.6 They are prophecies that people invoke, until they are more than prophecies. We predict that something like them should exist. They begin to come into existence. Being subject to them, our lives become more predictable. We depend on that predictability, and invest more in the structures. They grow.

Importantly: we are part of the world that changes. Our predictions are also about us, and about our predictions. We act internally to make our selves predictable.7 Our identities crystallize out of fluid informality. Adopting the context of an identity, we can force ourselves to be understood. Legible.

Sometimes, we have little power to change the world by leaning into our actions. But sometimes “I can’t change” is an illusion—a finger trap, a story we keep pulling on. How can we see past that?

Sometimes we do little more than observe. But we’re not passive observers: in observing, we act. We orient and reorient our bodies to seek out evidence. We point our eyes toward what we want to see, to force things to make sense. We may look away, when the tension seems unsolvable.

He was comfortable with this world, and he knew it. He knew it, and he liked it.

- Succession

We must predict as well as we can, or risk being overwhelmed and destroyed by forces we’ve not predicted.

We can improve our predictions in two directions: by acting to change the world to look more like our predictions, or by acting to change ourselves (our predictions) to look more like the world. On the one hand we can force our way, on the other we can be scientists.8

Too much science won’t do. In order to change the world, you cannot be too willing to change yourself. If you see that the world is one way, but you want it to be some other way, your prediction has to be stubborn. You’ve got to maintain the tension, the mismatch inside you between is and ought, so that it will drive your actions to change the is to be more like the ought. If you’re too much the scientist, you’ll eliminate the mismatch by simply acting internally to overwrite your ought with the is. I’ve seen the way things are. I’ve gotten used to it. (I’ve forgotten my dreams.)

Too much stubbornness won’t do, either. The world isn’t a blank slate for the inception of prophecies. There are actual constraints—stuff out there to be learned, stuff not easily changed. And who isn’t thankful for science? But it took us so, so long to arrive where we are. We’ve had had a similar biological capacity for intelligence for many thousands of years, right? We’ve spent almost all of our time leaning into what we already had.

Weirdly, we can become stubborn about the consequences of not being stubborn enough. I’ve wanted it to be this way all along, of course. And many literal scientists are clearly driven to their investigations by the stubborn urge to solve some problem or other. The two directions for improving predictions don’t correspond to two distinct identities—people who are entirely scientists, or people who are entirely stubborn. We’re all some mix. The two are entangled. They deeply reflect and layer upon each other.

Some kinds of stubbornness are more “built-in”, and hard to change no matter how stubbornly we think they ought to change. We can’t decide to not feel hungry, though we can learn to ignore the tension of hunger, and out-stubborn it. Maybe with enough time, stubbornness, and science we’ll alter our biology to eliminate the very feeling of hunger. Would we remember to eat then, or would we simply starve? Those rare individuals who are born unable to feel pain tend to die young. They lack that stubborn, driving tension that makes us act to save ourselves in the face of injury or illness.

Stubbornness versus openness gives us something like a trade-off between structure-forcing and structure-fitting.9 There is structure “out there” in the world, and structure “in here” in our bodies—which are also part of the world. We might prefer to say process instead of structure, but in any case the trade-off asks: How does the “in here” change the “out there”, and vice versa? How does evidence—information from “out there”—change us, and how do we resist being changed by it?

What’s the proper balance between stubbornness and openness?

We can re-frame a reach-harder/pull-harder/structure-forcing/stubborn strategy as predict harder that my predictions are true, which just means predict harder.10

I intensify my prediction—so, my action.

I escape this trap!—I pull harder.

I get my toy!—I reach harder for it11. When I go-harder, my wish is a little more likely to come true. But the world can also tell me no, not this time.

Maybe if I don't reach harder, predict harder, the other kid gets the toy. But maybe they do anyway. And maybe I’ve been predicting so hard that I keep on predicting I’ll get it, after it’s no longer possible.

Maybe I should've paid attention to something else. Seen something new. Escaped some trap.

Maybe learning comes too late.

Children are awesome explorers. Most of them will solve the literal finger trap before long.

In a very recent study, we gave participants a reinforcement learning task in which they could sequentially choose whether to place blocks on a machine. We told them that some blocks would lead to rewards and others to costs but did not reveal what differentiated the two. The actual rule was two-dimensional (e.g. black striped blocks were costly but white striped blocks or black spotted blocks led to rewards). After one negative trial, adults quickly assumed the most obvious rule, that a single feature differentiated the blocks (e.g. all black blocks were costly), and so avoided all the blocks with that feature. But this meant that they never received evidence that showed that the actual rule was more complex and so failed to learn the correct rule. As in other studies, they fell into a ‘learning trap’. Preschoolers, in contrast, continued to try all the blocks on the machine, and so learned the rule correctly.

- Alison Gopnik, “Childhood as a solution to explore–exploit tensions”

It helps that for the trickier problems which require a lot of experience, kids can have adults around to speed them along. Adults have already explored plenty when they were kids themselves, and imitation and language are powerful ways of sharing knowledge.12

Are there any super-adults around here that could speed us normal adults along? Many of us wouldn't trust them anyway. They're probably just trying to get me to stop pulling so they can steal my finger trap.

As adults, we become exploitative of the things we’ve already learned. Our lives can become tyrannically finessed. Pretend becomes obvious, tacit. We keep exploring, but our exploration—and by our designs, even our children’s—is bounded by our exploits. Our curricula, rules, governments...

Our best ways of doing things are effective because we lean into them, and force them into the world. But the more effective they are, the larger they become, the more exploitable and popular and normal… the less incentive to see beyond them. What was once mere prophecy can become a prison.

What’s innovation that isn’t marketable? If nobody has use enough to pay for it, who cares? Except: the superorganism of all of humanity has its own traps, which constrain the nature of the markets—the arenas we all play in. And how can we see past that? As individuals, we probably can’t, at least not fully and directly. It’s too big.

So how can we speed along our world-spanning child of a civilization?

We all live in intricate nests of mental and social bonds. Which of them are traps? Past some horizon, we cannot tell. Intelligence is whatever pushes the horizon further—gives us the vision and the option to escape. But do we, then?

Don’t we13 too often tend to pull stubbornly, coordinate stiffly, prolong history, mock intelligence, even though we’re probably dwelling just beyond a long-neglected hill, with who knows what freedom waiting in the next valley?

Too cynical? Well, as much as cynicism may be a trap… watch me escape!

Fake it ‘til you make it: Force your predictions on the world.

Be a scientist: Let the world force itself on your predictions.

These aren’t separate options, but deeply entwined.

Sometimes we fake it too hard. How do we know before it’s too late?

In the next part: meditation and Buddhism.

Of course the finger trap itself “interferes” with pulling. The trap violates the context in which pulling was originally learned. Here, we focus on the phenomenon where we get so into pulling that we neglect the change in context. What does being stubborn “protect” us from, here?

After you've escaped a few traps, it becomes easier to imagine that you should look for non-obvious solutions. So let's say our child is a particularly young and naive one, who hasn't learned the solution to the meta-finger trap yet, either.

Active inference is a manifestation of the free energy principle. In spirit, it’s akin to other theories of perception or action in which prediction (and Bayesian probability) plays a central and unifying role. See predictive coding and planning as inference.

Instead of tension, some would say impetus. It’s similar in principle to any gradient in a system driven by thermodynamics. The classic active inference explanation of why the hand moves in this situation, is that the brain sends predictions to the low-level motor control systems (spinal cord, skeletal muscles, muscle spindles) to the effect of “if you had reached for and grabbed the apple, this is what the proprioceptive sensations would be” and the mismatch in the actual and predicted sensations drives those low-level systems to contract the muscles.

I’m not saying they don’t depend (or “supervene” or whatever) on the stuff that physics or psychology speak of.

And governments, being made of people, act to make themselves and their subjects more predictable.

I want to emphasize that I use “scientist” in the most general sense: someone who is receptive to being altered by evidence.

Or to reverse the connotations: structure-giving (to the world), and structure-taking (from the world).

In the language of active inference: increase the precision of my predictions. This is related to Bayesian inference, and how a probability distribution whose density is concentrated in a small area is more preferential of one option over others.

Or my favourite model.

We as in coordinated groups of people. The market is much more intelligent than any individual, in principle. But it’s still made of people, and people scale weirdly. The problems I suspect mostly involve robustening at the social level, which stabilizes societies to outside interference, and constrains the incentives of individuals who might otherwise have explored autonomously. Robust coordination tends to the exclusion of insight. And the market “wants” to appeal to robustly coordinated groups of people—because that’s what it knows.