Pretend we're kids again.

It’s playtime. I reach for my favourite toy, but something unexpected messes with me. Some other kid's hand suddenly appears from the side and nudges mine, fudging my movement. I adapt and continue: I really want my toy. Maybe I get it. Sometimes the other kid does.

Similar incidents repeat several times over a few days of preschool. An adult watches from across the room. She notices that whenever the other kid is around, I tense up a little, and my movements are a little more jerky and furtive.

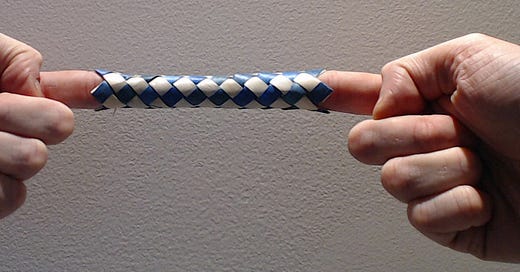

Have you ever played with one of these? Then you'd know their trick: once you put your fingers in, you can't simply pull them out. But that's probably what you'd try, your first time playing with one. It makes sense. Pulling is effective for many cases of trapped fingers—the usual situations you'd seen before. You pull, and the trap tightens as it lengthens. It grips your fingers harder. They won't come out! Ugh.

Now here's the interesting part: just like you have an action (pull) ready to exploit when your fingers are trapped, you also have a "meta-action" ready when you encounter frustration: try harder. So you pull even harder.

Eventually, you learn that the only way out is to relax. To fall apart. To see and act anew.

Have you ever watched for just how long someone can be stuck?

One recent summer afternoon, I visited some parents with a young child of about 4 years. We were eating and talking on the deck behind their house with a few other friends. At first, mom and daughter were away. They returned after a couple of hours.

Daughter was scared to come into the backyard and up onto the deck. Mom, who is one of the most understanding and gentle people I've met, carries daughter up onto the deck and sits with her for a while. The entire time, she's burying her face and half-crying, begging to be carried inside. Mom says she's free to go in—but she won't be carried. Mom reminds her that the rest of us are harmless. She doesn't seem to believe it.

Eventually she gets tired and goes in. For a time, she sneaks glances at us from the window. Before long, she comes back out and plays on the trampoline with her older brother, apparently unworried.

Near the beginning of the pandemic and my PhD, I consumed a neuroscience paper that lingered in my stomach. Before long, I was ruminating on philosophy… plenty of time for that, in 2020.

On the surface, the paper asked how we can move our limbs effectively when under the influence of unpredictable forces. But the results nudged me toward at a deeper principle—something I'd noticed in myself, and sensed in everyone. Not just the obvious movements of our bodies, but also the movements of our minds.

At first, the principle was nameless. I couldn’t speak of it. Chewing for a while on visions of muscles, I decided on a metaphor: clenching.

I wasn't the first. Also in 2020, someone wrote in public about a seemingly different topic—but really, pointing in the same direction—and said "unclench" in passing. I read their post in July 2023, and for a moment I felt disturbed. Frustrated.

I reached for my favourite toy, but the other kid had already grabbed it.

I'd wanted to write about these things myself! Frustrated, I questioned whether I should write at all. Some part of me wants to control, to own the act of explaining. To be original. To be the first to say.

Well, that's clenchy. A piece of me, caught by itself. A mental finger trap.

No longer. Time to go back outside—and maybe even jump on the trampoline.

Let's explore something old and wild. But new to your thoughts, perhaps… still new enough to mine.

What does reaching for an apple have to do with philosophy? What is attention? Can I be intelligent, but fail to learn? Why can't some of us stop thinking painful, hopeless thoughts? What is mental illness, and addiction? What about tyranny?

What happens if I let go?

Continue with the next part of this series!

minor note: this first post doesn't link to part 2 at the end rn